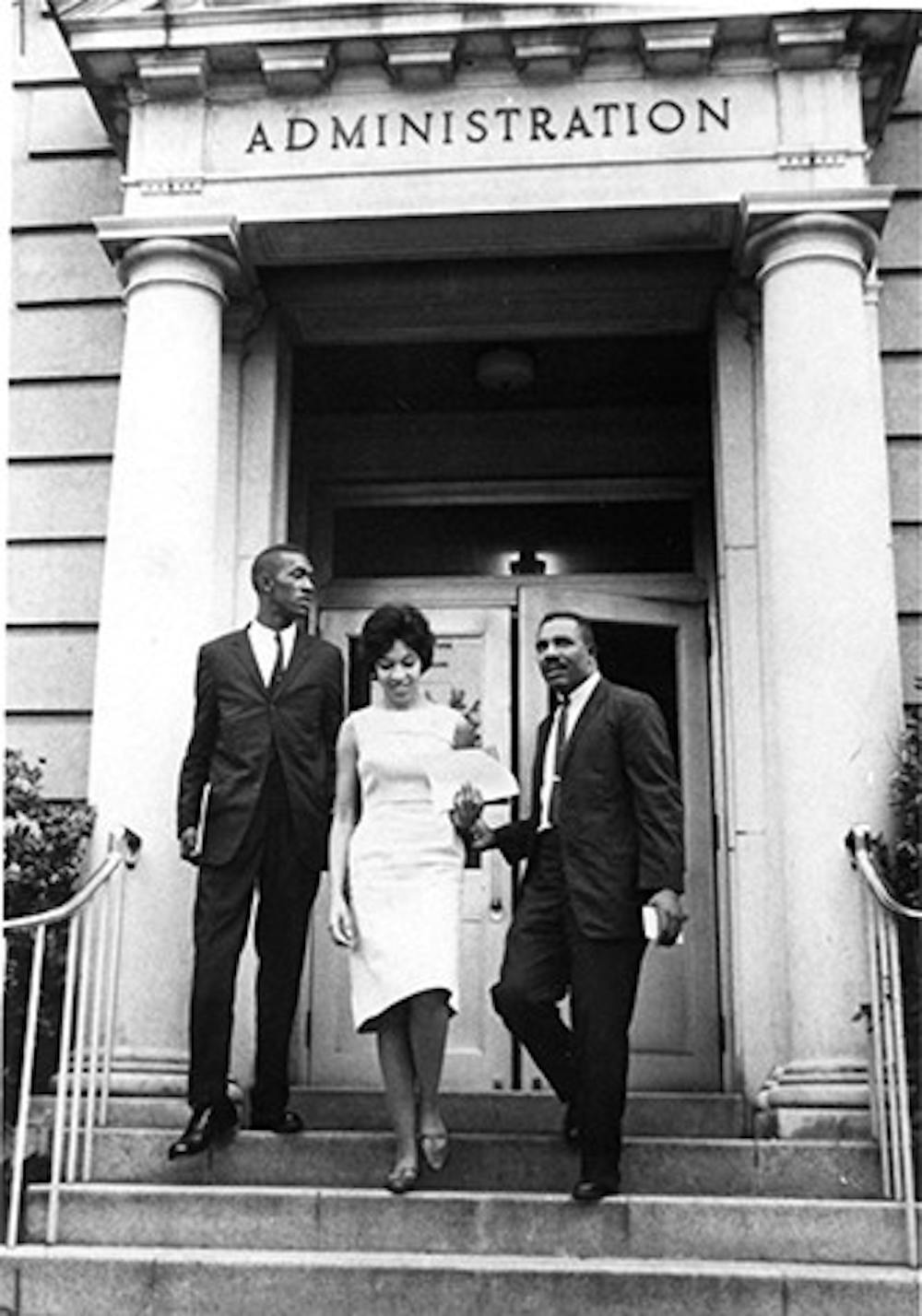

On Sept. 11, 1963, there were no riots. There were no federal marshals. There was no fight from the state government. Three new African-American students walked down the steps of the Osborne Administration Building, the first to do so since Reconstruction.

It happened only three months after Alabama Gov. George Wallace attempted to physically block African-American students from entering the University of Alabama and less than a year after white students at the University of Mississippi erupted into a deadly riot stemming from the enrollment of its first African-American student.

Henrie Monteith, James Solomon Jr. and Robert Anderson quietly desegregated the University of South Carolina. But the calm of the event was carefully calculated.

Where we’ve been

“USC and Clemson did not want to see themselves as other southern universities saw themselves,” said Valinda Littlefield, director of African-American studies and co-chair of USC’s Desegregation Committee. “The university orchestrated this calmness. There were certainly people who were not happy about it.”

The three students, especially Anderson, were often harassed by their white peers, and a cross was burned in the yard of Monteith’s aunt and uncle, Littlefield said.

“The line between peace and violence was a thin line. It came down to leadership,” said university President Harris Pastides. “Had there been a single student or community member who threw a rock or a Molotov cocktail, it could have ended very differently.”

Instead of the riots seen in states like Alabama, much of South Carolina’s desegregation fight happened in court. Six months after an appeals court ruled that Clemson had to admit African-American transfer student Harvey Gantt, the U.S. District Court ordered Monteith be admitted to USC. Solomon and Anderson followed quickly with applications to the university.

“Segregation and, truly, apartheid was just as ingrained in South Carolina as anywhere else,” U.S. Rep. Jim Clyburn, D-S.C., said. “But South Carolina displayed a certain degree of sophistication and enlightenment. South Carolina decided to take a much more measured role in its opposition to civil rights.”

Earlier that year, outgoing S.C. Gov. Ernest “Fritz” Hollings asked the state General Assembly and people across South Carolina to accept the desegregation of the state’s colleges and universities. “We have run out of courts,” Clyburn remembered him saying.

“It was an acknowledgment that he was going to recognize this country as being a country of laws and not men,” said Clyburn, a veteran of South Carolina’s civil rights movement.

And, instead of taking an active role in efforts to fight desegregation like his Alabama and Mississippi contemporaries, Hollings “did not add fuel to the flames,” Pastides said.

In the fight to allow white and black students to live and learn together, Hollings made all the difference, Clyburn said.

“It was very simple,” he said. “South Carolina had more enlightened leadership.”

Where we are

In 2012, 7,274 African-American students were enrolled throughout the University of South Carolina system. But for many of those students, as well as faculty, obstacles remain every day.

“Many of them still do not feel as if they are totally integrated into the university. In talking to some of them, I certainly get that that is their perception,” Littlefield said. “They still talk about racism. It’s very much part of any institution. Some [African-American students] experience racism. Sometimes it’s subtle, but sometimes it’s very abrasive, and they do know when they experience it.”

Many African-American students also feel pressure to achieve highly in the classroom in order to buck racial stereotypes and make professors and peers take them seriously.

“One of the biggest things I noticed when I first got here, coming from a high school that was 99 percent black, and then going to classes where I may be the only or one of the only black students, I feel like I have to work harder and that the expectations are higher,” said Aaron Greene, president of the Association of African-American Students.

The second-year public relations student came to USC from Orangeburg, where more than 75 percent of the population is African-American. At USC, only about 15 percent of students are African-American, and 42.2 percent of Columbia residents are. Orangeburg is also home to two of South Carolina’s five historically black colleges and universities.

But in a predominantly white institution like USC, African-Americans say they often find themselves as the only person in class who is not white, even in a 200-person lecture hall.

“I’m looked to as the black example (in class),” said Jasmine Gant, president of the Multicultural Greek Board and Zeta Sigma Chi Sorority, Inc. “When you ask a white person to speak, it’s their opinion and theirs alone. I have to be on my P’s and Q’s and make sure that I don’t fall into stereotypes. I don’t want to be the angry black woman. I don’t want to be the lazy black person who doesn’t do her assignments.”

African-American faculty members, too, sometimes feel the pressure to be an example. They are often looked to as liaisons to the local African-American community and are turned to by black students as mentors or even just a person “who looks like them,” Littlefield said.

“African-American faculty often talk about the amount of service that is required of people of color, women in particular, and that is also a double-edged sword,” Littlefield said. “The academic world says your research, your teaching, your publications — those are your markers in the academic world.

“At the same time, because you are the black female, the black male or any other group that is underrepresented, you end up with a second job. That job includes your connection with … the larger community that has felt left out of the ivory towers of academia, even though the university is in the middle of their community.”

Where we’re going

Henrie Monteith (now Henrie Monteith Treadwell) and James Solomon Jr. will retrace their steps out of Osborne today, marking 50 years since non-white students were first allowed to study at the University of South Carolina.

“It’s important to look back and view it through the black and white photos we have, but it’s also important to take a look at where we are and where we can go,” Pastides said.

While the proportion of African-American students at USC has doubled in the past 40 years, many are still calling for more action. While segregation is a long-gone policy at USC, some students say they see others separating themselves by race, accidentally or intentionally.

“The next step is unity. Dr. (Martin Luther) King put so much work in, but there’s still space between us,” Greene said. “This generation has to take steps towards unity. We have to unify campus as much as possible. I believe it is still an issue. You can see it on campus. You see it in Russell House, when people sit separately.”

A key to this unity is knowledge, according to Briana Quarles, vice president of the National Pan-Hellenic Council for Sorority Council, who serves as an EMPOWER diversity peer educator.

“I have a friend who is also in EMPOWER, and I love when she has those lightbulb moments, like, ‘I didn’t know how much privilege I had because I’m white,’” Quarles said. “You don’t see privilege if you have it. If people could see what we go through on a daily basis, if they could take a look through our eyes for just a day, they could see what we feel and why things need to change.”