Lynn Bozof’s 20-year-old son Evan was everything most college students want to be in his third year at Georgia Southwestern State University: honors student, student-athlete, healthy. But one day he called his mother complaining of a terrible headache, and, thinking this unusual for her normally healthy son, she told him to go to the emergency room. Just 26 days later, Evan was dead.

“One day he was healthy and the next he was in the ICU. He reached a point where he only had 5 percent of function in his organs, and he had to have all of his limbs amputated because of gangrene,” described Bozof, 17 years out from that fateful month in 1998. “Eventually he lapsed into about 10 hours of Grand Mal seizures, and the doctors told us he had irreversible brain damage and wouldn’t ever wake up. We then decided to pull the plug.”

But one of the most crushing blows was delivered shortly after Evan’s passing.

“After he died we found out there was a vaccine available that could have prevented this. My husband and I were left asking ourselves, ‘How did we not know this? He had everything that was recommended,’” Bozof said.

The disease was meningitis, caused by a meningococcus bacterial infection that first presents as flu or cold symptoms but can turn deadly in a matter of days or even hours. The vaccine was the MCV4 vaccine, marketed commercially as Menactra or Menveo. These vaccines work to prevent four of the five types, known as serogroups, of meningococcal disease including two of the most common types in the U.S.: Y and C.

Dr. Leonard Friedland, who serves as vice president of scientific affairs and public health at the pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline and boasts 10 years of experience as a pediatrician, highlights the unpredictability of the disease.

“The way it works is this bacteria tends to hang out in the nose; that’s where we normally find the bacteria that causes this disease. Many will have it in their nose and it won’t cause a problem, but sometimes it gets in the bloodstream and we can’t predict for whom it will,” Friedland said.

This unpredictability is a key component of why vaccination is so critical among key demographics and the general public, according to Friedland.

“There’s really no such thing as a mild case of meningitis,” he said. “Prevention is critical because treatment is often too late, and it’s really a pediatrician’s nightmare to have a child or young adult come in to the office with symptoms of meningitis and the next day they’re in the ICU.”

Friedland’s “nightmare” coming to life before Bozof's eyes is what drove her and four other parents to found the National Meningitis Association as a means of raising awareness about the crippling effects of meningococcal diseases and vaccination. Bozof is now the organization’s president.

“We realized that there are other parents out there who also don’t know. That was when we decided to start working to raise awareness,” she said.

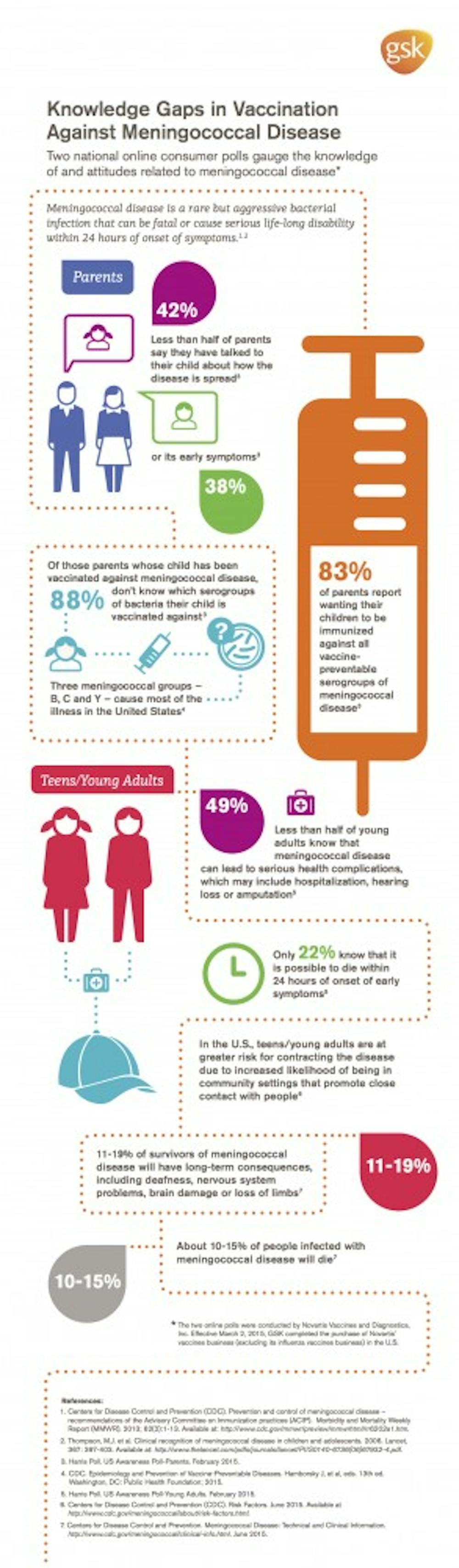

Bozof’s realization was an accurate reflection of public knowledge of meningitis and vaccination. A recent Harris poll found that 83 percent of parents want their children vaccinated against all five serogroups, but only 42 percent have talked to their children about how the disease is spread and only 38 percent have discussed its early symptoms.

College students don’t fare much better, according to the same poll. It found that only 49 percent knew that meningococcal diseases can cause “serious health complications” and only 22 percent knew they could cause death within 24 hours. These numbers are particularly troublesome in that young adults are a core demographic for meningitis.

“The epidemiology has been studied very closely and we see two peaks in the number of cases: very young children or infants and young adults,” Friedland said. “One of the reasons we see higher risk in demographics that tend to be crowded, such as college students or members of the military living in barracks, is that the sharing that happens allows the bacteria to spread more easily.”

While the aforementioned demographics as well as those with issues of immune deficiency are considered at higher risk, Friedland also made clear that any and all are vulnerable.

“But you can’t predict exactly who’s at risk. Two-thirds of MenB cases are sporadic in noncollege kids,” he said. “Everyone is at risk, that’s why vaccination is critical.”

“MenB,” or serogroup B meningococcal disease, has posed a particular problem to scientists and doctors for years. Despite being one of the three most common types of meningitis in the U.S., differences in the B bacteria’s structure meant that the MCV4 vaccine didn’t work to prevent it.

This has changed in recent years with the creation of new serogroup B vaccine, marketed commercially as Bexsero or Trumenba.

“I think it’s wonderful that there is now a vaccine for Serogroup B,” Bozof said. “It’s been a missing link for a long time with regard to prevention.”

Both vaccines types are recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, one of which is available to USC students at the Thomson Student Health Center, according to the center’s Director of Nursing and Patient Services Janet Jackson.

“We require all incoming students under the age of 21 to submit documentation of meningitis vaccination or to submit a completed meningitis waiver in compliance with the University’s immunization requirements,” Jackson said. “We strongly recommend both vaccines for our students.”

“These are vaccines we do offer when we set up at orientation. We see a lot of parents saying, ‘Hey let’s get this done while I’m here because you may not remember once I’m gone,’” she said.

According to Jackson and the Student Health Center’s Allergy, Immunization and Travel Clinic “there [have] not been any confirmed cases of meningitis on our campus within the past five years.”

Jackson also added that she has seen an increase in the number of vaccinated students here at USC during her tenure.

“It’s interesting; I’ve been here for about five years and it used to be that we’d get waivers flying in, but I’ve noticed more students coming in with the vaccines or coming to get the vaccines,” she said. “And I think that’s a good thing. It says to me these students or their parents or someone is paying attention and taking notice.”

Friedland noted that it has taken time to get the public’s attention with regard to adolescent vaccination but that paying attention is critical.

“Our approach to public health, particularly vaccines, has been focused on young children. The first recommendations for adolescents didn’t come till the 2000s, so there’s still an adjustment,” he said. “You see college students who go to bed one night not feeling well and they write it off as a cold, or staying up too late studying or at a party, but the next day they’re in the ICU.”

Given the chance to address parents in the same shoes she was when Evan went away to school, Bozof was clear in the message she would want to send: “Don’t think because this is a rare disease it won’t affect you; it’s right in your backyard."

Correction: A previous version of this story included Menhibrix as an MCV4 vaccine. Menhibrix is only licensed for serogroups C and Y in infants. The Daily Gamecock regrets this error.