The first time Charles McDew met a white person in the South, a policeman pulled him over at 1 a.m. in Sumter, South Carolina. It was Thanksgiving break, 1959. In Ohio, where McDew had been raised, he wouldn’t have been worried. But this was segregated South Carolina. He ended up in jail with a broken jaw. The next day, the black section of the train was full heading to Orangeburg. So he sat down in the white section — back to jail. When he finally made it into the city, McDew figured he could cut through a park to get to the safe haven of the historically black South Carolina State University campus where he had started as a freshman. But the park wasn’t desegregated, so he was sent to jail for the third time in two days.

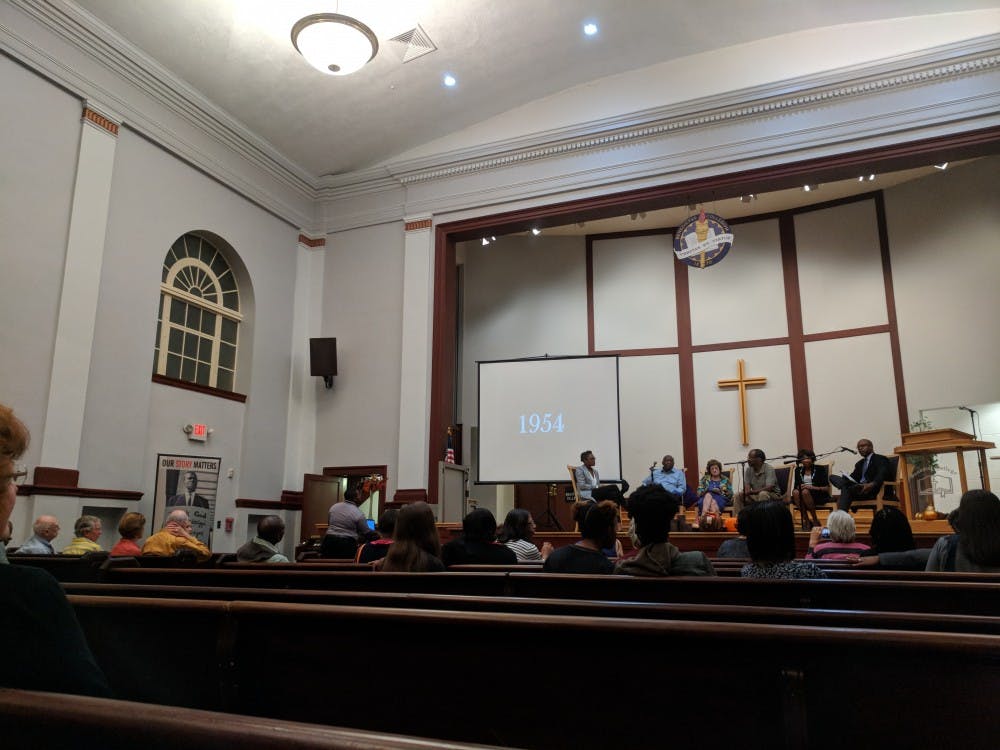

McDew shared his experiences Monday night in the Antisdel Chapel of Benedict College, part of a panel of early student leaders in the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. "We Who Believe in Freedom: Student Activism in the Civil Rights Movement" was jointly organized by USC, Benedict College and Columbia SC 63, a group collecting local civil rights history. But the panel, moderated by USC history and African American studies professor Bobby J. Donaldson, was as much about the current generation as the stories of South Carolina's civil rights figures.

Clarissa Gore, a third-year economics student at USC, asked the panelists if they felt current activists lacked the same motivation that drove early civil rights movements. Gore herself said she doesn’t see the drive among her peers.

“Our generation was handed everything on a silver platter,” Gore said. “They don’t focus on what the generation before us had to do.”

Before the event, students lined up to sign in for a class. As the start of the second hour rolled around, the pews became conspicuously emptier and emptier. The average age of the audience rose.

Annie Hackett Ritter, a Spartanburg native and ’61 Benedict graduate, said she hopes the lower levels of involvement among students today is because they’re studying hard. Other panelists were less optimistic.

Former SNCC program director Cleveland Sellers Jr. said that young people never ask him about his organizing experience or come to him for advice. There’s also a depiction in the history books, he said, that the struggle in South Carolina was less than in Mississippi or Alabama. Sellers’ frustration at the combined sense of being left out of the narrative and of little inter-generational engagement was palpable.

“You have to get the community to commit,” he said. “In order for there to be change, there have to be sacrifices.”

And for those who stayed, the stories of sacrifice were many. Ritter recounted the degradation her father, the community pastor, faced in taking on a second job digging ditches to support his family. Neither of her parents were able to attend even elementary school because it was 17 miles away and the bus only picked up white children. Sellers came home one day proud of earning a job at the grocery store only to be told by his father that he couldn’t take the job. He didn’t understand why at the time. Years later, he learned that the owner of the grocery store was also the leader of the local Ku Klux Klan. All three – McDew, Sellers and Ritter – participated in a sit-in at the South Carolina State House in ’61. The next month, the confederate flag was raised atop the seat of state government.

“South Carolina was worse than Mississippi,” McDew said. “Mississippi had the expectation. South Carolina had the reality.”

The state has a veneer of “polite Southern culture” that sheltered many of the terrible things happening, SNCC adult advisor Constance Curry said. Many of the police tactics, from setting loose dogs to fire hoses, were used in Orangeburg before becoming famous in Mississippi. The Orangeburg Massacre – when police killed three black students and injured 27 others – happened in 1968 before the Kent State shooting but received little media coverage. The state legislature never conducted an investigation of the events, something Sellers said haunts South Carolina to this day. Injured in the shooting, Sellers was convicted for charges relating to protests before the massacre. He was officially pardoned in ‘93.

Donaldson was recognized in October for his work around Columbia commemorating the civil rights movement of the city. He asked the panelists to explain why preserving the stories of the movement was so important.

“History can change your heart and change what happens in this nation,” Curry said. Events such as the Charlottesville rallies and NFL protests can be more richly understood with an understanding of history, she said.

Sellers urged students to study student activism to understand their own roles in history: “What legacy will you leave behind?”

One success of the event, Donaldson said, was simply bringing USC students who haven’t necessarily studied the civil rights movement onto the Benedict campus.

“Rarely is there a space for interaction,” he said. Although the administrations often work together, students from USC almost never visit the campuses of the two historically black institutions in Columbia.

As the event concluded and most remaining people filed out, a small group congregated at the front of the room. Veterans of the movement, they shared stories and reminisced. At least one student stuck around – Gore lingered to take a photo with Ritter. The Benedict alumna gave a bit of advice: “Go out there and continue the fight.”