When Lindsay Richardson was campaigning for student body president in 2014, a fraternity brother came up to her after a presentation.

“He was just like, ‘Yeah, I hope you know I really like your ideas, but I won’t be voting for you because you’re a woman,’” Richardson said.

She won, and became the second female African-American to serve in the highest student leadership position at USC. After Richardson left office and went to USC’s law school, three white men were elected.

With three African-American and three female candidates out of 11, the 2018 Student Government elections saw the most diverse pool in years. As a result, April 3 will see an African-American president and female vice president sworn into office.

But the diversity this year was unusual.

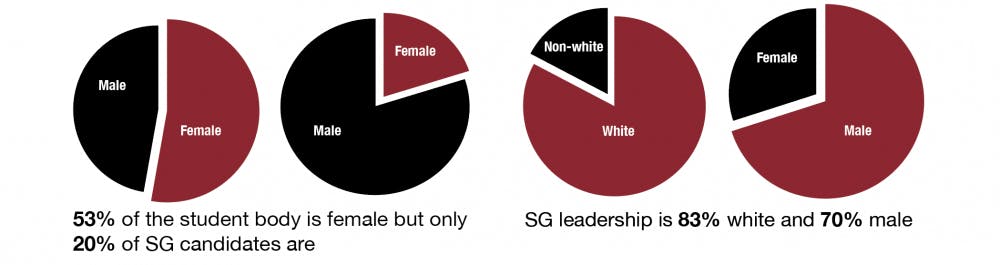

Only 20 percent of students who have filed in the past decade to run for executive positions in Student Government are women. That’s much lower than campus as a whole, where women make up 53 percent of students.

And while 14 percent of candidates over the last 10 years have been African-American, slightly higher than the percentage of campus, only 6.7 percent of elected executives were African-American.

“Universities are storehouses of ideas. And how can you have the best ideas if all ideas aren’t included?” chief diversity officer John Dozier said.

Candidates themselves don’t typically think about race or gender as a defining characteristic of the campaign. Yet for students across campus, simply seeing representation of people who look like them and understand their perspectives means a lot.

“For women, for African Americans, for people of color, to see someone in that high office, it’s just a reminder that they too can belong here, that they too can make a difference here, and that they too can be leaders,” Richardson said.

Richardson’s proudest accomplishment as president was starting Cocky’s Closet, a program for students who can’t afford formal business attire. She was motivated by students she knew that would benefit from the program.

“The pathway that was paved for me to win was paved by a lot of people that came before me,” Richardson said.

A history of firsts

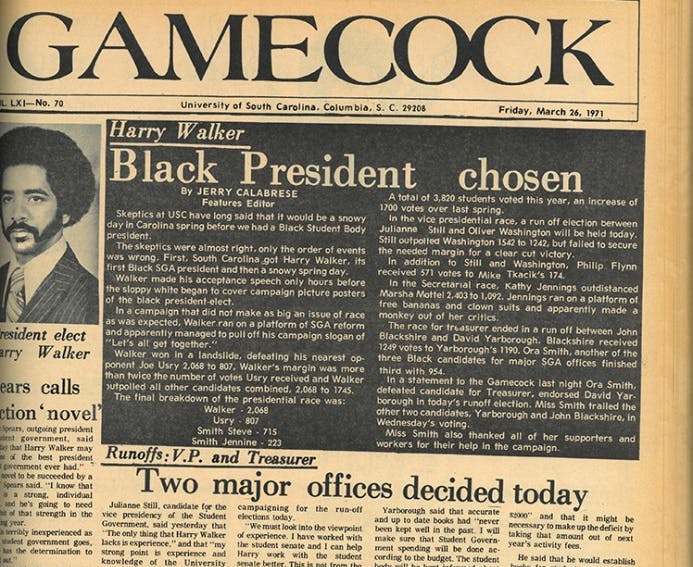

“Skeptics have long said it would be a snowy day in Carolina spring before we had a Black Student Body president,” read The Gamecock on March 26, 1971. “The skeptics were right, only the order of events was wrong.”

Harry Walker was elected in a landslide vote eight years after campus desegregated in 1963. A Student Government outsider known for his knowledge and poise, Walker became the first non-white leader since SG formed in 1908.

Dozier connected what happened on USC’s campus to the broader national climate — African-Americans have only been protected from discrimination since the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Another group protected under the landmark act was women. And two years after Walker, the first ever female student body president was elected — Rita McKinney.

“At the time I ran, I really didn’t think much about [being the first]," she said. "It just kind of didn’t really factor into why I decided to run."

While she wasn't the first female candidate, she was the first to win the presidency, drawing attention from local media. But like Walker, she preferred to focus on campaign points instead of her historical significance.

The first women stepped onto USC’s campus in 1895, the earliest of any institution in South Carolina. But none were elected to the highest student office for the first 66 years of SG history.

“In the American South, gender norms are a little more patriarchal,” women and gender studies professor Drucilla Barker said. According to Barker, differences in women’s historical role in the home are responsible for the stronger gender distinctions, especially when intersecting with race.

“For an African-American woman to be seen as a leader of men, that’s a real stretch for some people,” she said.

It took almost 30 years after the first African-American man, Walker, for the student body to elect an African-American woman as president — Jotaka Eaddy in 2000.

“There are a lot of stereotypes about how black women lead: that we’re typically aggressive, that we’re angry, and that’s not true at all,” Richardson said. “We’re often kind of put into a box that we can never be soft or compassionate, that we’re always kind of like the superwoman, but the angry superwoman.”

Other campus communities face similar stereotypes or societal pressures.

The LGBT community, present on campus since its creation yet hard to track historically, has seen representation in the highest office twice in recent years. Zach Scott, elected in 2004, was likely the first openly gay student body president.

And the growing Hispanic and Latino population on campus, which has risen to 4 percent, has yet to see an executive officer.

Today's struggles and successes

Since Walker and McKinney, SG has seen 12 African-American and 9 female student body presidents, or 40 percent of the 47 presidents since 1971.

Appointed Student Government positions see a lot of diversity. Under Student Body President Ross Lordo, more than half of officers are female and 14 percent aren’t white. When choosing the Freshman Council, SG leaders create a group that represents campus as equally as possible.

The senate, which is elected by college, also has been fairly representative over the past decade.

Yet the highest positions of president, vice president, treasurer and now speaker of the student senate have been predominantly white and male over the most recent decade — 83 percent white and 73 percent male.

Lordo said that he’s done his best to represent all parts of campus.

“It is important to be there, not just saying words or talking or tweeting or posting things,” he said. “To me, I found that I could be the best student body president by going to events — by going to the [Association of African American Students] cookout, or going to Birdcage, by immersing myself in different aspects of my community that I previously had no interactions with.”

The current officers are all white men, after Dani Goodreau stepped down in February from the vice presidency. All the officers the two years before were also all men. As a result, undergraduate students had only seen one female and one African-American executive officer, neither of whom were president.

Kathryn Stoudemire serves as Ross’s chief of staff and ran for ’18-’19 student body president. When Ross chose her to serve as chief of staff after she led the Momentum campaign, Stoudemire said that she was surprised to encounter men who still weren’t accustomed to women in positions of power.

One particular moment, when a man interviewing for a cabinet position that would report to her assumed she was a secretary instead of his potential boss, stuck in her mind.

“I thought that was not really a thing anymore,” she said.

Women have higher GPAs than men at USC, win more university awards and serve as the leaders of more behind-the-scenes organizations according to Jerry Brewer, associate vice president for development and Student Life facilities. Yet they tend not to aim for the highest positions in Student Government.

“There’s been a transition of getting females into the organization, but I guess it’s the next step of having them be able to be in the offices just the same,” Lordo said.

The problem of female representation at the top isn’t unique to USC.

In the SEC this year, five of the 14 schools have a woman at the student helm, although one was promoted from vice president. According to 2014 article from Inside Higher Ed, about a third of top-tier colleges have female student body presidents.

Universities like Princeton have created committees to study the issue, while others have used training programs like Elect Her that lead workshops for female students considering running for Student Government.

USC hasn’t had any continuous effort to encourage women to run, although there have been a few sporadic efforts throughout the years.

At USC and in elections across the country, though, women show up to vote in larger numbers than men. In the past two SG elections, about twice as many women as men voted.

Barker said that women on campus are more likely to vote because “things that affect everybody often affect women a lot more.” She used the example of campus safety — everyone worries about it, but female students tend to be more aware of the dangers of walking around intoxicated or alone.

Barriers to entry

There are a lot of reasons that could prevent students from filing to run for executive office, from fear of failure to not having the money. Serious executive candidates spend anywhere from $1,000 to $2,000 on campaigns. The Daily Gamecock asked all 11 of this year’s candidates how much they spent. Three candidates declined to provide a number. The others ranged from $120 to above $2,000, with higher spending not necessarily correlated to getting the win. In total at least $15,000 total was spent, on everything from banners and pizza to professional photographers.

For students paying for school or relying on limited family support, finding the funds to run can be difficult.

In the past, USC has tried different systems such as limiting spending to $1,000 and requiring candidates to hand in receipts.

Other universities still enforce a limit. Clemson University caps spending at $500 per ticket, with another $500 of donated materials allowed. Other schools, such as Ohio State University, have caps as high as $4,000. According to Stoudemire, though, a lot of schools do see candidates spending more than permitted.

The system was impossible to enforce, according to Brewer. He favors the current “free market system” where candidates are free to make spending decisions without oversight, presuming that the best ideas will always win out.

Dozier was surprised that spending in SG elections reaches the thousands.

“I would advocate strongly for us as a campus to find ways to reduce or get rid of that … barrier to participate in Student Government, because representation matters,” Dozier said.

Being on a ticket can save some money, according to Stoudemire, because candidates pool resources and buy merchandise and websites together.

But beyond economic cost, running takes a mental toll. Students have to be prepared to face the spotlight and criticism from a population of 35,000. And then, at the end, the money and countless hours can be for nothing.

A lot of students, especially women, simply don’t want to be president, Stoudemire said. Most of the women in Lordo’s cabinet are also involved in Greek life and see themselves as “contributing factors, not leaders” in Student Government, she said. And while research shows that men tend to decide to run on their own, women run after people suggest that they should, according to the Inside Higher Ed article. With few female role models in campus leadership of in the state, South Carolina women simply don’t get the same exposure as men to politics, Barker said.

The university is making steps to provide more diverse role models, with the percentage of professors who are African-American increasing from 5 percent to 6.2 percent since the 2016 protest on campus according to Dozier. USC has also hired a female provost, and the new vice president of Student Life is a woman. Nationally, a record number of women have filed to run for public office in 2018, according to EMILY’s List.

All those changes will help more diverse students pursue Student Government leadership, according to Richardson.

“Seeing someone who doesn’t necessarily fit the white male president image," she said, "is a refreshing reminder that you too can be a leader.”