Civil rights at the University of South Carolina is marked by early reception of African American students and faculty, quick regression and eventual integration.

From 1873 to 1877, the majority of the student body was African American, black trustees were appointed to the university’s board and Richard T. Greener, who is commemorated with a statue outside Thomas Cooper Library, was hired as the first black faculty member.

“When you look at the roster of students from 1873 to 1877, you’ll find some of the most gifted African-American students and intellectuals in the country,” history professor Bobby Donaldson said in 2013 to the university’s news outlet.

However, those four years of progress came to an end with the election of Gov. Wade Hampton. The university was closed at the end of the 1877 academic year, only to reopen three years later as an all-white institution.

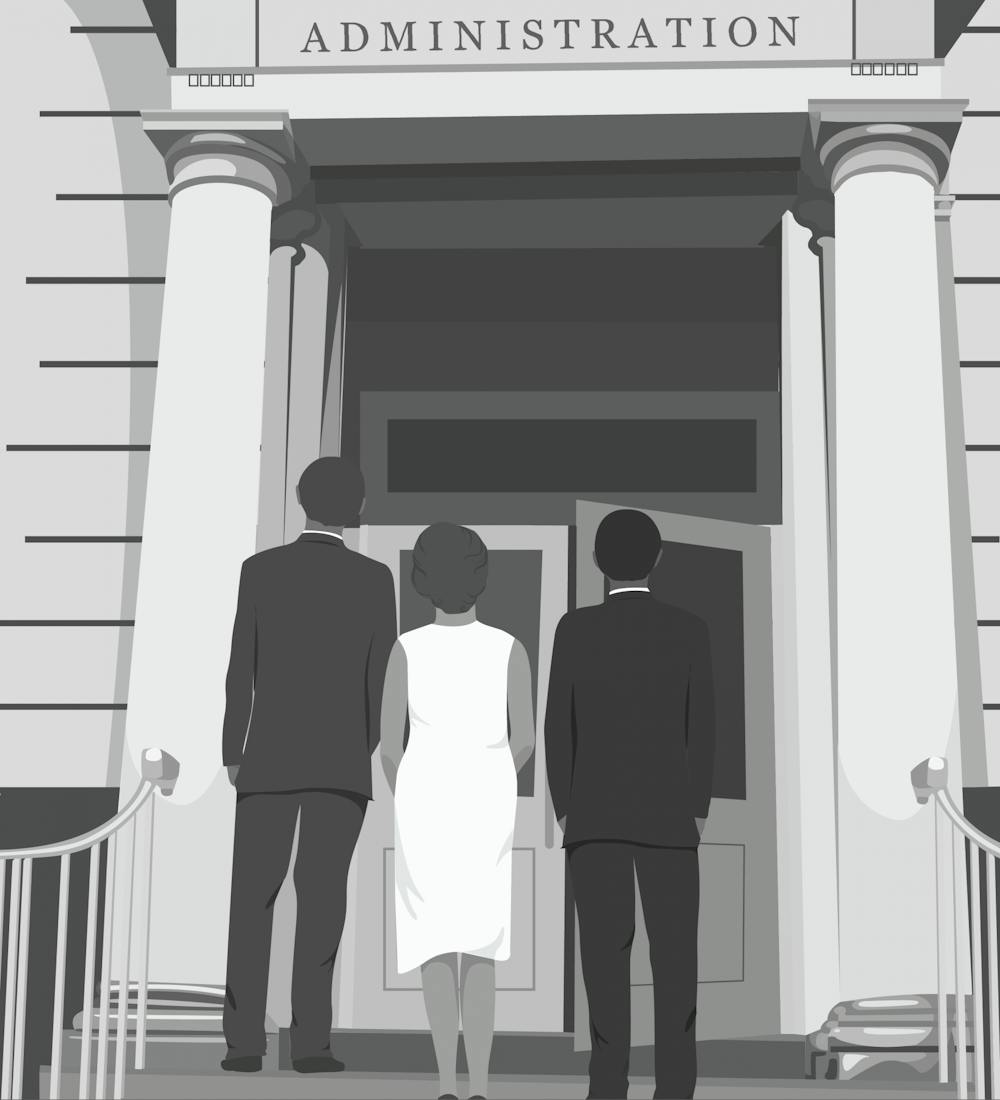

USC remained that way until 1963, when Robert G. Anderson, Henrie Monteith Treadwell and James L. Solomon Jr. became the first African American students to enroll at USC since the 1870s, effectively permanently integrating the school for the modern era.

Challenging educational barriers

Deciding to attend college was not as simple as submitting an application in the 1960s. Treadwell said she had to go through legal proceedings to receive a court decision, which would ultimately require the university to grant her enrollment.

“Then I think the more difficult process for me personally was, did I really want to go?” Treadwell said.

To help guide her decision, she looked to her family and the elders in her community. Treadwell was no stranger to activism. Today, national historical markers honor the home of her aunt, Modjeska Simkins, for her civil rights activism and the site of the Nelson School, a school for African American children founded by Treadwell's grandmother, Rachel Hull Monteith. Treadwell’s own mother participated in a lawsuit that helped African American teachers achieve pay equality with their white colleagues.

However, as inspired as she was by her family, Treadwell recalled the pressure she felt to attend USC did not come from them, but rather the community at large.

“I think the people who persuaded me more so were the older African American women who asked me to really consider going, and those are the voices that are still with me today. They wanted me to go, and I respected their opinions,” Treadwell said.

After her historic enrollment, Treadwell went on to make history a second time after becoming the first African American student to graduate from the university since 1877, earning a bachelor’s degree in biochemistry.

Robert G. Anderson began his studies at Clark College in Atlanta, but he joined the struggle for desegregation when he transferred to USC. While he didn't graduate from USC, Anderson went on to earn a degree in professional social work from Hunter College in New York.

James L. Solomon Jr. earned his bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Morris College and his master’s degree in mathematics from Atlanta University before being admitted to USC to continue his graduate studies in mathematics.

Integration faces backlash

At first, Treadwell’s uncle thought the loud boom outside his home on the night of Aug. 27, 1963, was nothing more than a "jet plane" flying overhead. It wasn’t until officers found a crater in his front lawn that the darker truth became apparent.

Treadwell's uncle said he had heard media outlets describe him as the father of Henrie Monteith Treadwell, implying that the bombing might have been meant for the residence of his niece, “I think it’s somewhat related to the fact that my niece might be enrolling at the University of South Carolina this fall term.”

While that attack was certainly the most extreme reaction to her impending enrollment, Treadwell said the more interesting backlash came from those in the African American community. She remembers the anonymous calls she would receive from those urging her not to attend USC.

“At that time, many people in the African American community were not sure that they wanted change, or perhaps they feared change. But change happens anyway,” Treadwell said.

While Treadwell said she did not experience any direct racism on the campus itself, she didn’t have much social interaction either.

“Mine was an isolated experience,” Treadwell recalled. “But it did not bother me, and perhaps has really left me with a strength that I would not have had. It is sometimes necessary to be alone in order to achieve, in order to focus, and so I am grateful for that experience.”

Treadwell and Solomon remember the days when people would bounce basketballs outside Anderson’s window all night, making it impossible for him to sleep. Or, when young men would knock on his door at 2 a.m., shouting obscenities before running away.

Treadwell said, “Bob Anderson was really ran away from that university. And I am wondering whether there are others who, if not totally run away, are not able to thrive at the highest levels because of subtle discrimination that still occurs. And I know it still occurs. I think everybody knows it still occurs. The question is, when do we say enough? Enough. It should have ended long ago."

Overcoming discrimination

However, the three students never lost their nerve and went on to accomplish great feats for themselves and their country.

Solomon became a career public servant, with roles in various state government positions such as division director at the Commission on Higher Education and the commissioner of the Department of Social Services. For his commitment to his community, he was awarded the Order of the Palmetto, the highest award given to a resident of the state, by both Governors Richard Riley and Carroll Campbell.

Both Anderson and Solomon served in the military. Solomon did six years in the Air Force before his time at USC, while Anderson served in Vietnam after graduation. Anderson’s experience in the military later led him to work in the Veterans Administration for 12 years after retiring from a long career as a social worker in New York.

Anderson eventually returned to USC for the 25th commemorative banquet, where Solomon remembers Anderson saying, “Jim, I’m so glad I came back. This changes my whole perspective of USC. I feel so much better about this school.”

Treadwell went on to receive a masters in biology from Boston University, a Ph.D. in biochemistry and molecular biology from Atlanta University and completed post-doctoral studies in public health at Harvard University. She now works as the director of Community Voices and a research professor at the Morehouse School of Medicine.

Treadwell has said about her historic time at USC: “It was not important for me to be admitted. It was important that all African Americans meeting admissions criteria be admitted. Ending discrimination based on color or race was the real issue for me. I was just a ‘wedge,’ and I had a supportive family and community.”

Treadwell said the university has done a good job "keeping issues of race, racism and separateness before the public," but there is still more to be done.

"I know that there is pushback among some students around the whole issue of race and racism. That needs to stop. And if it does not stop, I have little confidence that any of us in this nation, regardless of color, or gender, will do well. I believe that harder times are on the way, unless we decide to join our efforts. You may not want to join my hand, but join the effort toward human and social justice," Treadwell said.