Systemic racism in America has had long-standing effects on the Black community's ability to receive medical assistance and healthcare, which is now resulting in more Black people getting sick and dying from COVID-19 than other races, the CDC said.

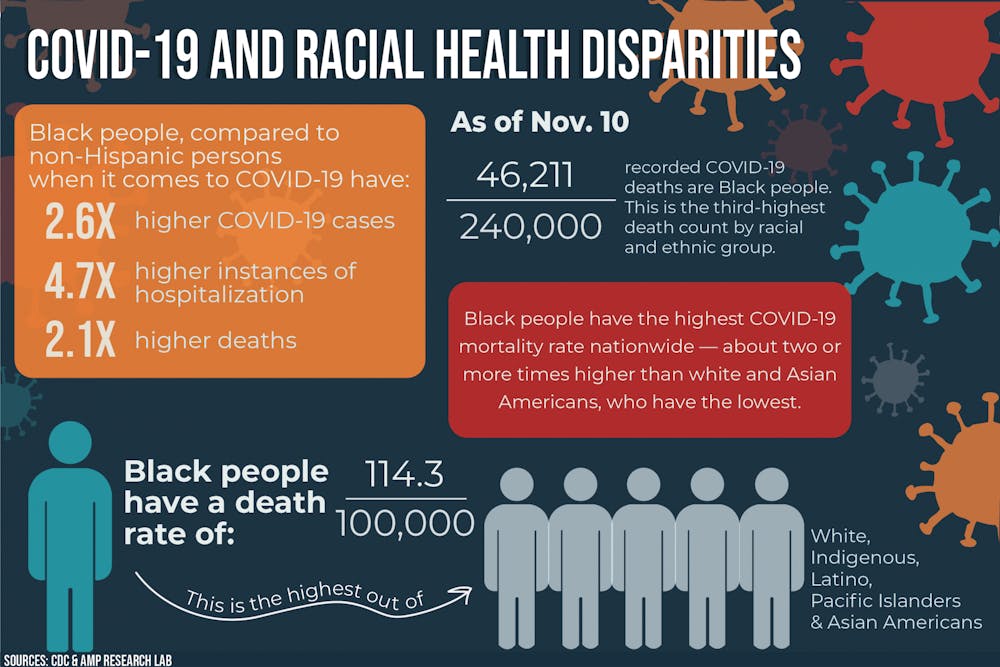

According to The COVID Tracking Project by The Atlantic, Black people are dying at 2.1 times the rate of white people. Its research found that, per 100,000 people by race or ethnicity, Black or African Americans accounted for 110 deaths, while white Americans only accounted for 52 deaths.

Factors that contribute to social and health inequities that the Black community faces include discrimination, access and utilization of healthcare and disparities in education, income and wealth, according to the CDC.

Monique Brown, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics in the Arnold School of Public Health, said COVID-19 has magnified racial health disparities that already existed.

"These inequities exist, and COVID-19 is really just a way in which these disparities are being highlighted even more so," Brown said. "Black populations make up 27% of the South Carolina population, but they account for close to 50% of the COVID-19 deaths."

Brown said these disparities exist due to the societal barriers that Black people face.

"It goes back to basically access to care. And even research has shown that Black populations tend to have lower-quality healthcare compared to white populations. So, there's the idea of structural racism that may impact the disparities that we see," Brown said.

In South Carolina, due to the large presence of rural communities in the state, the difficulty of receiving access to healthcare and assistance is even more exaggerated.

"Access to care is also lower in rural areas compared to urban areas, and this is also magnified for Black populations as well. So, when we look at South Carolina being a rural state, that even lowers your access to care," Brown said.

This lack of access to care increases the likelihood of underlying diseases in Black populations and other minority groups, which ultimately makes the effects of COVID-19 more severe. Melissa Nolan, an infectious disease epidemiologist, clinical epidemiologist and associate professor in the Arnold School of Public Health, said because minorities are more likely to have underlying diseases such as hypertension and diabetes, rates of hospitalization and morbidity are high.

"Having that puts you at a higher risk for severe disease because you are already in an immunocompromised state, so your immune system isn't quite where it should be to help battle it," Nolan said.

According to Nolan, minorities' "daily living scenarios" also put them at a greater risk because of the greater amount of people they come into close contact with regularly.

"The more times you are exposed, the more likely your chances of getting a disease," Nolan said.

Anthony Alberg, the chair of the Epidemiology Department at USC, said although the Black community's risk of contracting COVID-19 and risk of hospitalization from COVID-19 are about same when compared to other minority groups, Black people face a higher mortality rate.

"There's actually fairly comparable risk of developing COVID-19 say in African American, American Indian and Latino groups. They are all elevated compared to non-Hispanic whites and of similar magnitude in risk of disease and risk of hospitalization from disease. It's in mortality that African Americans have a stronger risk, of more than double the risk, of dying compared to non-Hispanic whites," Alberg said.

Alberg said explanations for these pre-existing conditions and disparities are deep-rooted in societal structures.

"There are historical reasons for the social differences that we see, the differences in socioeconomic status and so on that are contributing to these factors of living in more impoverished areas that might have greater exposure to air pollution and those sorts of things that are contributing here," Alberg said.

Brown said a solution to these racial health disparities is to increase access to care in vulnerable communities.

"One thing that can be done is to provide equitable healthcare for all. So, in respective of racial or ethnic background, in respective of socioeconomic status in terms of trying to provide healthcare that serves all and not just certain people," Brown said.

As students prepare to leave campus for Thanksgiving break, Nolan encourages students to protect their families by getting tested for COVID-19 through the free SAFE testing on campus before returning home.

"Even if you don't necessarily come in contact with minority populations or vulnerable people, you know, we would still encourage you to get tested because you never know what kind of contact you're going to have with someone. Even at the gas station, you could accidentally infect someone," Nolan said.