A shiny, kelly-green cigarette vending machine sits at Richland Library Ballentine. It looks more like a vintage jukebox than a standard vending machine, with its five-foot stature. But, looking closer, stacks of something inside are visible, ready to drop into the hands of an eager customer at the pull of a handle. This little machine does not sell cigarettes to library-goers, but tiny art.

The refurbished cigarette machines are called Art-o-mats. They are filled with art relatively the size of a pack of cigarettes, dispensing them to anyone with $5.

Artists working with Art-o-mat use their art to connect with people all over the country. They also have the creative challenge of making something that fits within such small dimensions. Art in the machines range from notebooks, to glass jewelry, to paintings on wooden blocks to little puddles made of resin.

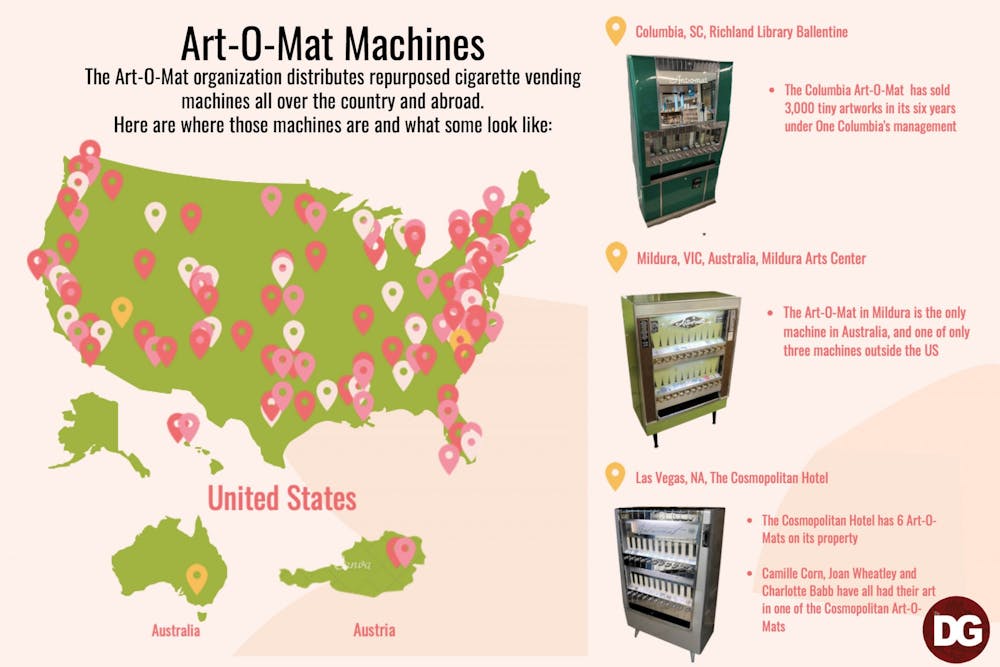

The business model is simple, inspired by a project Clark Whittington — founder of Art-o-mat — created in 1997 using his own photography in Winston-Salem, NC. Whittington receives the cigarette machines from people who “don’t know what to do with them.” Art-o-mat then repurposes the machines, sticking their logo on the front. Every machine is unique, which adds to the project’s artistic flair. The machines are then distributed all over, in almost all 50 states and all the way to Europe and Australia.

Lee Snelgrove, former executive director of One Columbia, the company that leases art vending machines from Art-o-mat, has heard many stories about the curiosity the machines provoke in its users.

“Stories of like, when it was at (a Columbia bar), people complaining about the weird European brands of cigarettes that are being sold out of the machine, like no, that's art,” Snelgrove said.

Once people figure out what it is, they love the concept.

“You hear stories about things that people found in it that are really exciting,” said Snelgrove. “Just some fun pieces that artists have created, and people get really enthusiastic about it and build their collections.”

One Columbia, a non-profit helping to promote public art in the area, oversees transporting the Art-o-mat to different locations around town and filling it with art from Artists in Cellophane.

“The whole mission is to promote the arts in the town,” Whittington said. “So, (One Columbia) is using Art-o-mat to help liven up these unconventional venues and actually make it easier for the public to kind of experience the Art-o-mat.”

Artists in Cellophane is a subset of the Art-o-mat organization that deals directly with the artists involved. Artists send a tiny-art-prototype, and once approved, they make hundreds — thousands in some cases — of tiny artwork to be distributed in machines throughout the country and abroad.

Artists who work with Art-o-mat are all over the country, but many are from the Southeast due to their proximity to the organization’s birthplace in Winston-Salem, NC. Spartanburg, SC. has a small concentration of Art-o-mat artists, about seven of them in the small town.

Joan Wheatley, a Spartanburg artist, has been working with Art-o-mat since 2018. She loved her experience so much that she pestered her friend and fellow Spartanburg artist Charlotte Babb for over a year and a half.

According to Wheatley, Babb was an instant success.

“She is unbelievable. Her very first check was $1,000,” Wheatley said. ”I said, 'What? are you kidding me?' She said to me one time, ‘I'm so glad you bugged me for a year and a half.’”

Babb’s first paycheck is even more impressive knowing artists only receive $2.50 from each piece they send to Artists in Cellophane. Since Wheatley convinced her to join the game, Babb has turned making tiny art her full-time job in retirement, sending thousands of pieces to Art-o-mat every year.

“I sent (Artists in Cellophane), I think it was 94 pieces, which is what fits in a priority mail mailbox, every week from June through the middle of December,” Babb said.

That means Babb made 2,345 individually, hand-made pieces of tiny art in six months. She earned $5,000 that year.

The key to being successful as an Art-o-mat artist relies on producing something small, cute and easy to make, according to Wheatley. She said her crocheted hair clips were a hit.

“I can’t sell enough of those,” Wheatley said. “They’re quick and that's what you want for Art-o-mat, you don't want something that's going to take you a long time and cost you a lot of money.”

Babb was not the only Spartanburg artist Wheatley recruited. Debbie Harris, who knows both Wheatly and Babb, also got into the business.

“I joined, and then I told Debbie, right away she said, ‘This is advertising, if nothing else,’” Wheatley said. “I mean, I'm not going to advertise in Bozeman, Montana, but that's where there's an Art-o-mat machine.”

Three of the Spartanburg Art-o-mat artists, Wheatley, Babb and the first of the group to work with Art-o-mat, Camille Corn, each make between 1,000 and 3,000 pieces of art each year. They all said they find crafting the tiny art pieces therapeutic.

“I'll take different pieces of glass and put them together,” Corn said. “and then when I put them in the kiln and melt them all together, you never know what they're going to look like when they come out, and it's kind of like Christmas!”

Another exciting part of the Art-o-mat process for the women is finding their art all over the country.

“I've had at least one piece that was sold in Australia, which I have never been to,” Babb said.

“I have stuff at the Smithsonian. Isn't that a riot?” Wheatley said.

“It's really exciting. I mean, it's kind of like a guest appearance on TV, and you're like, ‘Hey! That’s me!’” Corn said.

They each said their favorite aspect of being an Art-o-mat artist is connecting with the people who buy their art. Many Art-o-mat artists write their email addresses on the back of their art and encourage customers to contact them with information about where they bought it. The artists see their work reach an audience that may not have been possible without the machines.

“I guess some of them really like it because they’ve gone through the trouble of taking a picture and sending it to me, and that's almost as good as getting paid,” Babb said. “I've always wanted people to know who I was, even though I'm very introverted, so I feel like I've had an influence on people out there and they like me.”