For a few weeks every summer, one million purple birds descend on Lake Murray's Bomb Island. The birds only stick around long enough to feast on insects, forming clouds so thick they're often called a "haze," before migrating south for the winter.

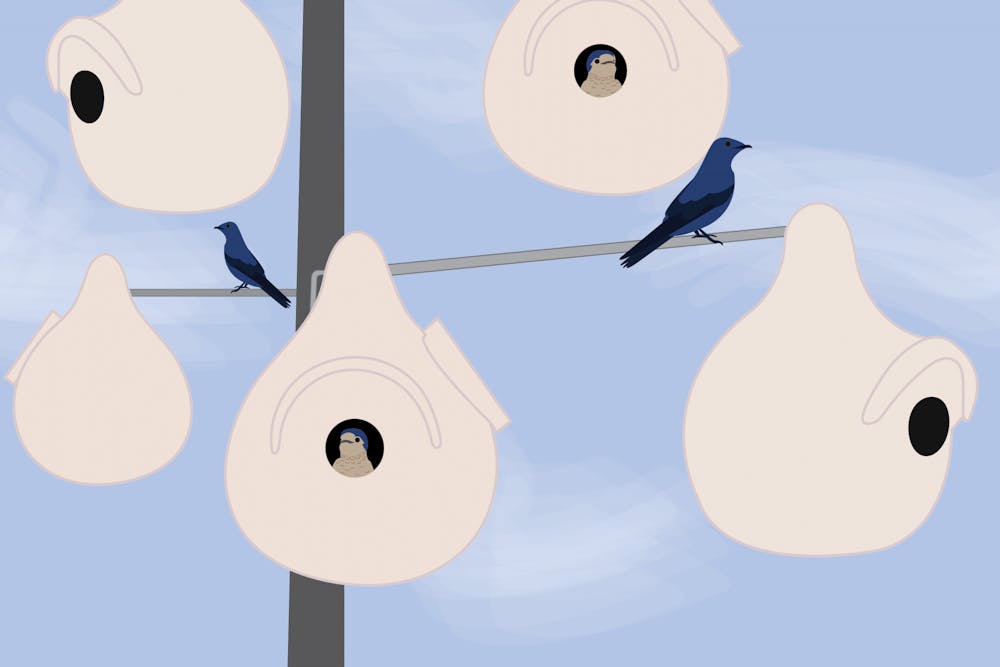

Nearly 90% of these birds, called purple martins, wouldn’t survive without human intervention. Artificial nests are what keep this species’ population alive.

This fact drove young naturalist Zach Steinhauser, a Lake Murray native, to investigate the life cycles and care behind the purple martin in his documentary titled “Purple Haze.”

“When I heard the fact that purple martins are only born in birdhouses, I was like, ‘I’m going to school for this and I don't even know about this.'" Steinhauser said. "That was the light switch moment."

Speaking with experts at the Purple Martin Conservation Association in Erie, Pennsylvania, Steinhauser was able to understand why these birds are so reliant on humans.

Naturally, purple martins are cavity nesters — birds that nest holes made by woodpeckers and other animals. Observing this, Steinhauser said, Indigenous Americans would hang gourds for the martins and other cavity nesters around fields while also allowing forests to remain intact. Europeans, on the other hand, tended to clear-cut forests.

“We didn’t give much opportunity for the forests to regenerate well enough to allow for the martins to keep identifying natural cavities as their habitats,” Steinhauser said.

Steinhauser's documentary explores the link between purple martins and humans, with the hope of finding martins that have retained their instinct to nest naturally. The film took Steinhauser around the Western Hemisphere following the birds’ migration, from the Amazon rainforest, to nests in Tucson’s saguaros', to the world’s largest purple martin nesting colony in Alabama — a family-owned establishment containing over 2,200 artificial nesting cavities.

The film’s focus isn’t on the range of Steinhauser’s travels, though, but rather the localized actions of people who care about the purple martin.

“It's a call to action to get people to notice what's in their backyard, to care about what's in their backyard and to want to do something to conserve the wildlife and the environment around that,” Steinhauser said.

For those interested, birding supplies and information can be found at stores like Wild Birds Unlimited or through organizations like the South Carolina Bluebird Society and Audubon South Carolina. Purple martin supplies specifically can be found on the PMCA's website.

Steinhauser's message of community conservation resonates with the mission of Camp Discovery, a Blythewood nonprofit that held a screening for the film on Aug. 20.

The camp focuses on environmental education, through summer camps, school outreach programs and more, said Executive Director Amy Ellisor.

The goal of these programs is to provide students with a “nature-to-your-doorstep” model, where the environment is something they’re always in.

“They can extend that learning whether they're here, at school, their grandma's house, on vacation. So we're trying to create the future generation of environmental stewards,” Ellisor said.

This education involves a very hands-on approach. Including students surveying forests for species of rare birds. One such bird, the chimney swift, is an endangered bird that has made its nest in several places around Camp Discovery.

No purple martins have been seen at the camp, though — not yet, anyway. Steinhauser said he plans to build artificial cavities for the facility.

“Camp Discovery has been protected so well that most of these 116 acres are raw and natural, that in three years we would probably have purple martins,” Ellisor said.

Installing homes for purple martins is easier said than done.

“Trying to attract purple martins is a labor of love,” said Steinhauser in the pre-screening panel at Camp Discovery. “It may take a couple years of tinkering and moving things around.”

Purple martins are known as “colonial nesters” — essentially, to become a purple martin landlord, six units is a good start, with additional increments of six being added on over time. Steinhauser also recommends having at least 30 feet of open space away from trees or structures, making attracting these birds to an urban setting difficult.

Those interested in bird conservation in Columbia shouldn't feel discouraged, though. Many other cavity-nesters have fewer requirements for a suitable home.

Glen Hendry, a board member of the South Carolina Bluebird Society who attended the screening, specializes in building habitats for cavity-nesting birds across the state, not just purple martins. He recommends a distance of only 6-8 feet from trees or structures, to avoid snakes and other predators.

“I wouldn’t say guaranteed, but very high probability if you put a box in your yard, that you're going to have bluebirds or some other kinds of cavity nesting bird use that box,” Hendry said. “If you build it, they will come.”

Between pollution, predators, and human-caused habitat loss, Hendry is happy people have been able to positively affect these birds. The South Carolina Bluebird Society alone has put up more than 1,700 birdhouses since coming into existence in 2010.

"Usually, mankind is the reason for the decline. In this case, mankind is the reason for the rebound," Hendry said.