The discovery of hazardous chemicals in our drinking water raises concerns about water quality and safety here at the University of South Carolina and in the community. Some contaminants, such as forever chemicals, are more well-researched, but the population deserves more information about lesser-known dangers in the water.

Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, a group of chemicals known as PFAS and tabbed “forever chemicals,” are stubborn chemicals that resist breaking down in the environment and in the human body — hence their nickname. They have been drawing the attention of scientists and politicians for decades over their potential health impacts, but there are more dangerous — and more common — contaminants in the water that South Carolinians need to be concerned about.

Susan Richardson, a chemistry professor at the University of South Carolina and former EPA chemist, said forever chemicals are not nearly as concerning as another family of chemicals commonly found in our drinking water — disinfection byproducts.

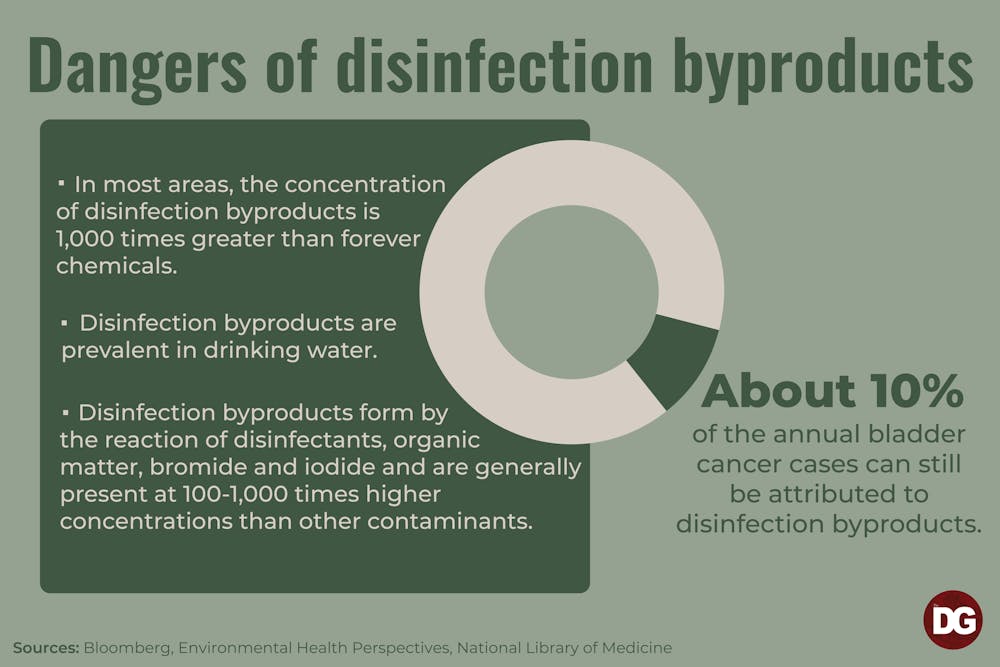

Disinfection byproducts are chemicals that are produced when certain disinfectants are added to drinking water at water treatment facilities in order to eliminate harmful pathogens. They form by reacting with organic substances that naturally occur in water, such as salts and decomposed plant matter.

Forever chemicals, in contrast, originate in industrial facilities and are used in making items like nonstick cookware, waterproof clothing and firefighting foam. They find their way into our drinking water through wastewater from manufacturing facilities and human disposal of products containing them.

This major difference between the two contaminant types creates unique challenges to detection and monitoring, Richardson said.

“(Disinfection byproducts) are different from other contaminants because they’re formed during drinking water treatment, and they’re formed from natural organic matter,” Richardson said. “Disinfection byproducts are ... not made by a company for any particular reason, so it can be harder to identify them for those reasons.”

Richardson said that years of epidemiological research on forever chemicals have yet to build sufficient evidence that connects perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances to health issues beyond high cholesterol, a condition that could also result from unhealthy eating habits.

Disinfection byproducts seem to have been overlooked amid the hype over forever chemicals. The EPA added 29 forever chemical compounds to its fifth Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule list, a program that collects data on the occurrence of unregulated contaminants in drinking water, but no disinfection byproducts made the list. Yet our drinking water has as much as 1000 times higher concentrations of the latter, Richardson said.

There’s still so much we don’t understand about these contaminants, like their long-term health effects, interactions with environmental factors and the full extent of their presence in our drinking water. Richardson said she is also concerned there are other toxic compounds in the same family that haven't been discovered yet.

Several epidemiological studies link prolonged disinfection byproduct exposure to bladder cancer, birth defects and miscarriage, but there is an overall shallow body of research, which can impede public awareness regarding the dangers in our water and hinder informed decision-making. Without a clear understanding of disinfection byproducts, there are likely disparities in exposure for certain populations, which is a major environmental justice concern.

Why are forever chemicals in the spotlight, then? The name itself is "cute," Richardson said.

Forever chemicals are also produced by large corporations, and concerned citizens have become outraged to learn that these companies have been polluting waterways for decades. South Carolina Attorney General Alan Wilson sued several companies earlier this year, including 3M and DuPont, for knowingly polluting rivers and lakes for decades, and the South Carolina Department of Health said in October that it detected elevated levels of contamination in freshwater fish from 18 different waterways throughout the state, including the Broad and Congaree rivers.

However, forever chemicals are being phased out of industries, meaning they are no longer being produced in the same numbers, so perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substance levels are decreasing in both human blood samples and in the environment, Richardson said.

The use of fad phrases like "forever chemicals" recklessly oversimplifies a complex issue. By drawing so much attention to perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, public discussion around chemical contaminants in our drinking water lacks nuance that can impact regulatory decisions. Though we may continue to hear about forever chemicals in the news, disinfection byproducts and other contaminants aren't any less of a threat.

Disinfection byproduct levels here in Columbia are still fairly low compared to other places, according to Richardson. She said using a carbon-based filter, like a Brita, for drinking water and changing the filter every two months can help eliminate many disinfection byproducts,and drinking tap water is also still better than drinking from plastic water bottles, which contain high levels of other toxic chemicals, such as polyethylene terephthalate.

Research into disinfection byproducts and other lesser-known contaminants needs to be prioritized, allowing all South Carolinians to make informed choices about protecting our health, as well as the environment, for generations to come. Fully understanding the hazards posed by the chemicals lingering in our water, food and air is powerful knowledge that should be easier for us to know and access.