For decades, Assembly Street has stood like a scar across Columbia’s heart — dividing communities, disrupting daily life and daring anyone who crosses it to trust their safety to luck. It’s a corridor of contradictions: too wide for safety, too choked for efficiency, too essential to ignore, yet too broken to trust. Trains idle across intersections. Cars roar through nine-lane stretches. Sidewalks vanish without warning. Traffic lights don’t account for people — just movement.

On April 2, that broken system killed someone.

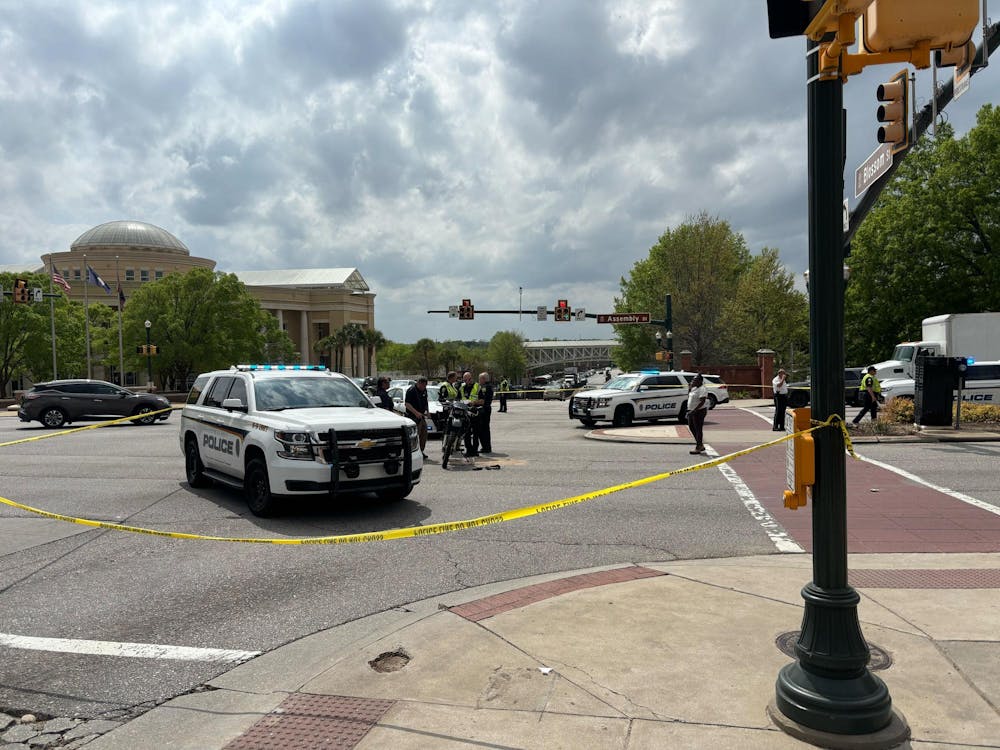

Nathaniel “Nate” Baker, a 23-year-old USC student, died when a pickup truck struck his motorcycle at the intersection of Blossom and Assembly streets. The driver fled and now faces charges, including hit-and-run resulting in death.

While the driver's actions were undeniably tragic, the incident also highlights deeper systemic issues. Assembly Street is often recognized as a high-risk area, where roadway design prioritizes vehicle speed over safety. In such environments, pedestrians and cyclists often face heightened danger simply by sharing the road.

Baker lost his life on a stretch of road that, by design, compromises the safety of all who use it. And yet, we’ve known this for years. Baker’s death underscored what some pedestrians have long suspected: this street doesn’t just inconvenience people. It endangers them.

The street that shapes behavior

Assembly is dangerous not because of a single flaw — but because of the compounding effect of many flaws. Wide lanes invite speeding. Ill-timed lights create traffic bottlenecks. Freight trains often sit parked for 20 minutes or more, cutting off intersections and forcing both drivers and pedestrians to improvise. And improvise they do: running red lights, swerving through gaps or trying to beat the gates.

This isn’t hypothetical. It’s habitual. Over time, a kind of normalized recklessness has emerged on Assembly — not out of malice, but out of adaptation. And that's where design becomes deadly.

It's important to understand that Assembly facilitates reckless driving. It rewards impatience and punishes caution. It demands rapid decisions in a chaotic environment. That's not bad luck. That's a system failure.

In a 2024 interview by WLTX, former USC student Macayla Anderson describes crossing Assembly as "not safe at all". She’s not exaggerating. There’s no guarantee that cars will slow down, and pedestrians have to gamble on limited signals and worn crosswalks. It’s like the street teaches you to gamble. And if you lose, you don’t get another try.

"The safety of our students walking to and from campus is a top priority. USC has started a master planning process that works to improve walkability on campus. Current projects focus on major thoroughfares like South Main and Wheat streets," University Spokesperson Collyn Taylor said in a statement.

Infrastructure failure — in real time

Our community’s leadership has acknowledged the dangers of Assembly Street for years. In fact, during a meeting in 2022, Columbia City Council approved $600,000 for a pedestrian safety project between Pendleton and Lady Streets, citing longstanding safety concerns. But our response has often felt like treating a bullet wound with a Band-Aid. A sidewalk here. A study there. A promise of long-term redesigns buried beneath short-term political delays.

Now, community leaders finally have a real shot at transformation. In January, Congressman Jim Clyburn announced a $204.2 million federal grant to fund a long-delayed rail-separation project. This would eliminate dangerous at-grade crossings — possibly by elevating train tracks above Assembly or lowering the roadway beneath them. The South Carolina Department of Transportation (SCDOT) has begun early conceptual designs. Meanwhile, Columbia also secured a separate $16 million estimate to improve pedestrian safety along Assembly, though only $3 million has been secured so far.

That’s a crucial step. But it’s not enough on its own — and it won’t come quickly.

Columbia's residents can’t wait five or more years for community leaders to get their act together. Students still have to sprint across multiple lanes of traffic, drivers confront freight trains that sit parked at random times and cyclists navigate a landscape that barely acknowledges their existence. This isn’t a rare inconvenience. It’s a daily risk.

Baker’s death wasn’t just tragic — it was the result of a system that repeatedly failed to act, despite knowing the dangers. Again and again, this community has chosen the status quo over safety.

The human cost of inaction

According to the SCDOT, major pedestrian safety upgrades on Assembly will cost $16 million, with only $3 million now in hand. State Representative Seth Rose (D-Richland) insisted that simply ignoring Assembly is not an option. Students shouldn’t have to risk their lives to reach an education.

On game days near Williams-Brice Stadium, close to 80,000 fans pour into the area. Sidewalks vanish, traffic piles up and trains frequently crawl through or block roads altogether. Gameday vendor Kylin Doster told The State in 2023 that cars “rarely stop” for pedestrians. The result? Families with young children, elderly fans and students balancing tailgate supplies all crammed into narrow shoulders and forced to trust their luck.

That stress is normalized simply because it’s familiar. But familiarity doesn’t make it acceptable.

Politics as an obstacle course

The timing of the grant coincides with national uncertainty. The newly-elected Trump administration recently signed executive orders pausing parts of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. Elon Musk, newly appointed head of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), has cut funds for public projects deemed unnecessary.

Although the rail separation project has not yet been defunded, it leaves us to question if it could get caught in bureaucratic limbo.

Columbia City Council members, like Tyler Bailey, said Assembly Street is a top priority, but acknowledge that federal and state cooperation is critical. Clyburn helped secure the rail project funds, but if those funds stall, we don’t just lose a project. We lose time. We lose trust. We risk more lives.

History shows what's possible

It’s easy to feel like Assembly has always been broken. But our community has tackled tough infrastructure projects before. In the 1980s, the city partially relocated downtown rail lines, transforming a grim switchyard into Finlay Park. Old rail corridors became the Vista Greenway. That shift took vision, funding, and follow-through — and it worked.

Assembly Street could see a similar revival. Consolidating the CSX and Norfolk Southern lines could eliminate at-grade crossings, with a projected cost of $275 million to $300 million, according to the South Carolina Daily Gazette. It’s a heavy price tag, but Clyburn’s grant was meant to close the gap. Chris Dorsey, part of a group restoring Capitol City Stadium, is optimistic; he says upcoming sidewalk extensions will create a continuous pedestrian path from Wheat Street to Williams-Brice Stadium.

Fix what we can now

Big projects can take years, but small steps don’t have to. Former state senator Dick Harpootlian (D-Richland) has proposed short-term improvements: curb bump-outs, adjusted traffic signals, enhanced crosswalks and lane reductions. Changes like these may not solve everything, but they give drivers and pedestrians critical margins for error.

And margins matter. When a driver makes a mistake on a well-designed street, they slam the brakes. On Assembly, they can kill.

City officials and local residents have admitted that Assembly is a “mess”, while Columbia's downtown master plan acknowledges its current configuration stifles both safety and growth. The question is whether those admissions will translate to concrete, immediate action.

No more next times

Our city was born to be bold — founded as one of America’s first planned cities, laying out broad avenues to spur growth. By the mid-1800s, rail lines connected us to Charleston, Charlotte and Augusta, fueling economic potential. Yet that ambition seems to have fallen short on Assembly, where nine lanes can turn an ordinary commute into a game of survival.

Nate Baker lost his life on a road shaped by decades of questionable design, political inertia and a willingness to let the familiar remain unchallenged. The longer we wait to fix Assembly, the more likely it is that someone else will meet the same fate.

We need to stop asking whether Assembly can be fixed. We need to ask what it says about us if we refuse to try.

Columbia has already proven that bold, well-funded efforts can transform entire districts. Now, it faces one final crossing — between ambition and action. If we let community leaders stall here, we risk more than time. We risk more people like Nate. And we lose the right to be surprised the next time this street claims another life.