For the last decade, the most prominent landmark in downtown Columbia hasn’t been the Statehouse dome or the pristine Horseshoe — it has been a dry, rotting concrete cliff face where a waterfall used to be.

When I was a child, Finlay Park was the exception to Columbia’s expected mediocrity. The cascading wall of water roared like a river, drowning out the noise of the traffic — an escape from the hustle and bustle of the city. It felt like a legitimate city center: a place where the community actually converged rather than just passed through.

I went back a few months ago, just before the construction fences went up. The silence was heavy. The waterfall had been dead since 2015, the basin empty save for decaying leaves and plastic bags. The grass had surrendered years ago.

Now, Columbia has committed nearly $25 million to fix it again.

City leaders are taking their victory laps, framing this renovation as a new chapter filled with security upgrades, amenities and destination playgrounds. But what is left unsaid in the press releases is that we are simply buying back what we allowed to be stolen by incompetence. We have had the park, the vision and the money before. Yet each time, we let it slip away the moment the ribbon-cutting photos were taken and the unglamorous work of maintenance began.

To understand why this renovation feels less like a solution and more like a recurring fever dream, you must look at the history of the park itself. This isn't the first time Columbia has betrayed this specific plot of land.

Over a century ago, this site was Sidney Park, a Victorian jewel with public gardens, ponds and a small zoo, according to Richland County Library. It was the green heart of the city. But in 1899, in a move of shortsighted industrial lust that would make modern developers blush, the city leased it for $30,000 to make way for a freight terminal.

Citizens sued, but the bulldozers came anyway. The promised industrial boom never materialized, and for decades, newspapers described the site as a crater-like depression — a scar on the city’s face where a park used to be.

It took Kirkman Finlay Jr. to reverse that neglect. He saw potential in the crater, and by the 1980s, he pushed through an ambitious vision to reclaim the land, hiring legendary landscape architect Robert Marvin. By 1990, the park reopened, and for a fleeting moment, it worked. Hootie & the Blowfish played there, and the Friday night concerts were packed.

But Finlay Park was always held together by individual willpower, not institutional policy. It relied on a champion, not a budget or a codified process.

After Finlay died in 1993, the city’s attention drifted. By the mid-2000s, the maintenance budget was quietly suffocated. When the waterfall pumps failed in 2015, the city simply shrugged. Fixing a pump isn't sexy; you can't hold a press conference for a maintenance repair. So, they let it rot.

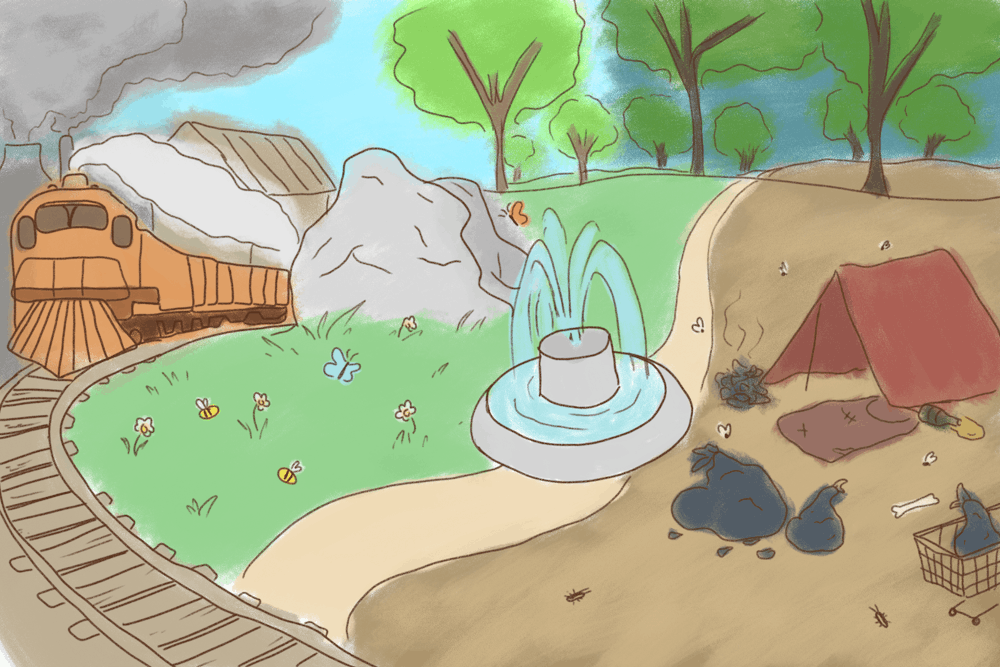

In the vacuum of leadership, the park transformed. As the water dried up, the desperate moved in, and a few years later, Finlay Park had become the city’s de facto outdoor homeless shelter. Charities served meals on Sundays; benches became beds. As one man living there told a reporter in 2020, "It’s always been like this."

And he’s right; the park was treated as an overflow valve for society’s social failures. Instead of funding housing or mental health services, we effectively outsourced our social safety net to a park bench, and then acted surprised when families stopped showing up.

Now, as property values in the Vista soften and the crater becomes an eyesore for developers, the checkbook has suddenly reopened. We spent $25 million to revitalize the park, and simultaneously, the city is spending taxpayer funds on a rapid shelter village of 50 small pallet homes nearby.

For that amount of money, based on typical South Carolina construction costs, we could have built hundreds of units of permanent supportive housing. We could have gotten closer to addressing the root cause of the homelessness crisis that occupied the park. Instead, we are buying a $25 million aesthetic bandage and a temporary fix. We are stapling a renovation onto a social crisis and calling it progress.

The "new" Finlay Park undoubtedly looks beautiful. The water flows, and the security cameras hum. Property values will likely tick up, and politicians will pat themselves on the back for saving downtown once again.

But the renovation doesn’t fix the culture of neglect that killed the park in the first place. Buying a new car doesn't matter if you refuse to fill the gas tank.

Parks only work when a city understands that public space is a trust, not a line item to be slashed during the next recession. Columbia has shown no such understanding. We treat public infrastructure like disposable cutlery — use it until it breaks, throw it away and buy new when the shame becomes too public.

So go to Finlay Park, and enjoy the renovated fountain. Remember that Sidney Park vanished when the city traded public space for a freight yard and that Finlay Park decayed when maintenance and housing slid down the priority list. If this version is managed the same way, we will be standing right back here, staring into the crater of neglect.

If you are interested in commenting on this article, please send a letter to the editor at sagcked@mailbox.sc.edu.