Let's call AI what it is: intellectual cheating. When students let AI think for them, they’re not just unfaithfully completing an assignment; they are robbing themselves of the struggle and thought processes that make education meaningful. Sure, a machine can spit out coherent sentences, but it cannot teach you to argue, empathize or imagine. If this quiet epidemic of outsourcing thought continues, the next generation of students will only be fluent in copying and illiterate in all else.

Of course, every generation of students has reached for shortcuts, from CliffsNotes to Wikipedia, but AI represents a leap beyond assistance into replacement. Unlike past tools that summarized or explained, today’s large language models generate entire arguments, complete with citations and structure.

In fact, a 2023 survey found that more than half of college students have used AI for coursework. While some limited their use to brainstorming or editing, a significant share admitted to submitting AI-written passages as their own.

The consequences are already visible. Employers consistently rank critical thinking and communication skills among the top qualities they want in new hires, yet they also report that these are the very skills graduates lack.

If students spend their formative years delegating these tasks to machines, their mental capabilities will perpetually decrease. Early data suggest this is not hypothetical; recent unemployment figures show a widening divide between recent graduates and the broader labor force.

Even universities are divided. At USC, the Division of Information Technology recently partnered with OpenAI to provide ChatGPT to all students, faculty and staff. Now, it seems nearly every professor includes an AI policy in their syllabus, trying to balance access with accountability.

When used wisely, AI can be a powerful tool for efficiency — helping with formatting, grammar checks or data summaries. But when it becomes a substitute for original content, it undermines the very cognitive growth that higher education is meant to cultivate.

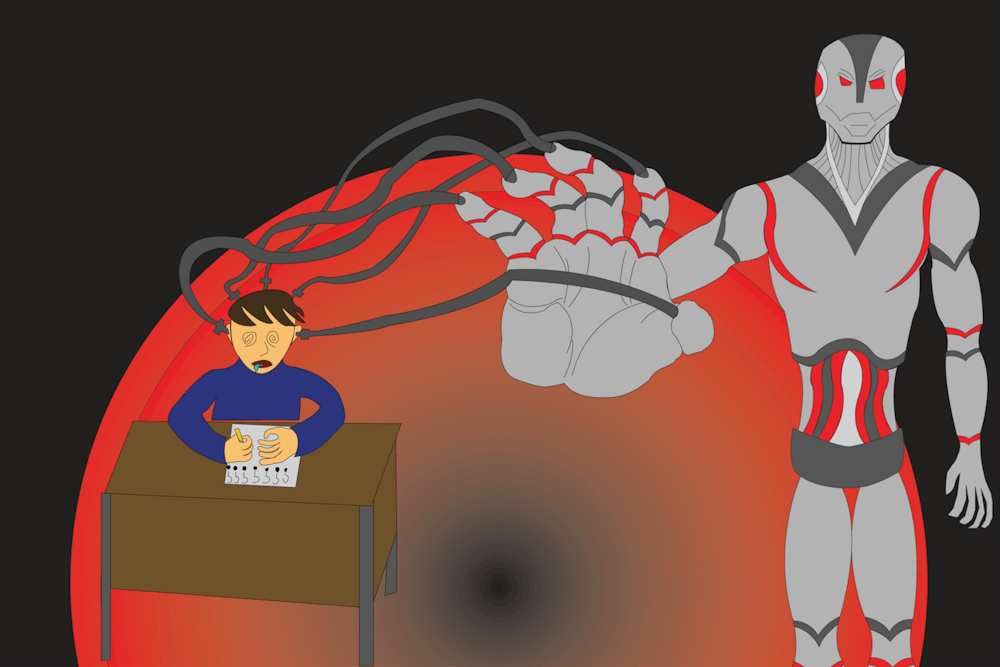

Neuroscience research makes this risk tangible. An MIT-linked study measuring brain activity during essay writing found that students using AI showed a significant reduction in the neural activity tied to understanding and storing information.

Their metacognitive loops, or the brain’s ability to monitor and regulate thought, were disrupted, and their neural connectivity weakened. As neuroscientist Jared Cooney Horvath said, “Using AI to help learners avoid the tedious process of memorizing facts is the best way to ensure higher-order thinking skills will never emerge.”

Creativity suffers just as much as critical thinking. In controlled experiments, letting writers use AI-generated ideas made their stories look more polished, especially for less-experienced writers, but those stories often converged toward the same predictable patterns.

The net effect was higher individual scores but lower collective originality. Researchers Anil Doshi and Oliver Hauser found that AI tools initially improved the individual creativity for non-creative writers. But this came at the risk of "losing collective novelty," as the similarity between the AI-produced works was much higher compared to fully human-created works. This develops a social dilemma where sameness spreads because it’s easy and instantly rewarded.

The neural account behind that sameness is devastating. A recent study tracking writers with EEG found that participants who used ChatGPT showed markedly lower brain engagement across multiple regions and struggled to recall what they had “written” afterward; 83% of the large language model (LLM) group couldn’t quote from their own essay, compared to 11% in the non-LLM groups. Effectively, the machine did more work while the brain did less and remembered less.

Meanwhile, student use isn’t negligible; it’s mainstream and climbing. By January 2025, about one in four U.S. teens (26%) reported using ChatGPT for schoolwork, double 2023’s share. Additionally, in 2025, 38% of adults 18-29 reported using ChatGPT at work, the highest of any age group. The number of adults using AI at work will only continue to grow, as graduating students take their AI-shaped habits into the workplace.

Institutions are racing to catch up, though sometimes stumbling. In 2025, Google tested a Chrome “homework help” button that could parse on-screen quizzes and feed AI answers, triggering immediate backlash from universities concerned about normalizing shortcuts during assessments.

AI will reshape far more jobs than it fully replaces. The World Economic Forum predicts significant task automation but emphasizes integration over substitution. Employers expect a sizable share of tasks to be automated, yet adaptability, reasoning and communication remain top human differentiators. In practice, that means graduates will be expected to use AI and to outthink it.

So the guideline is simple: treat AI as an accelerator for low-value chores, not a surrogate for your mind. Reserve it for citation formatting and grammar checks while you do the hard parts: research framing, argument construction, evidence selection, revision for logic and the final pass in your own voice. That balance allows you to reap benefits while avoiding impairment to mental capabilities, which are vital to securing future success in the workplace.

If you are interested in commenting on this article, please send a letter to the editor at sagcked@mailbox.sc.edu.