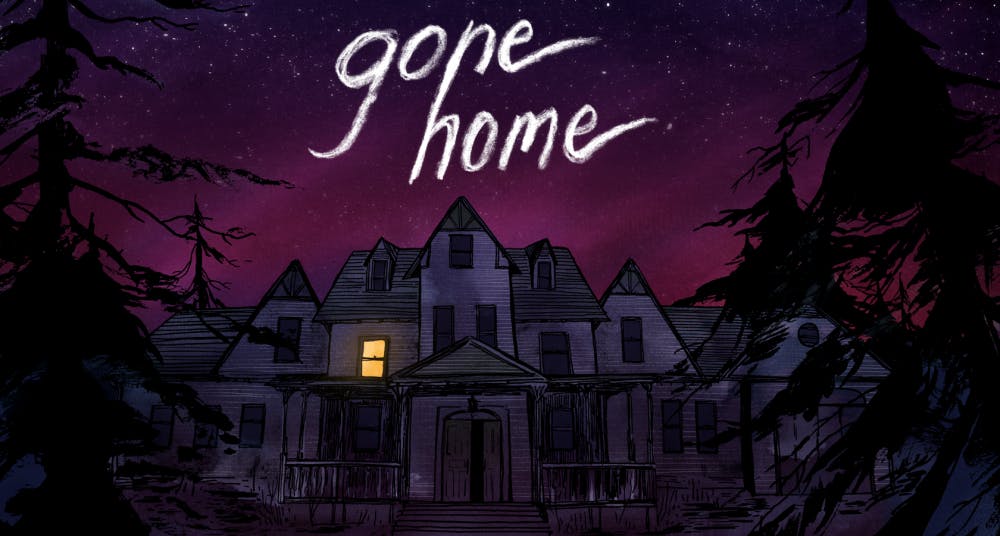

Realistic graphics give players a visual storybook

It’s June 7, 1995, when 22-year-old Katie Greenbriar comes back home to Oregon after a yearlong trek through Europe.

Other than the steady pouring rain against the windows and a severe weather alert buzzing from the family TV, the house is silent when she arrives.

Mom and dad are gone, and Katie’s younger sister, Sam, has left a note saying she’s run away.

The answering machine in the foyer has Katie’s message to her mother, still unchecked. Then there’s another message from a young girl in tears, pleading Sam to “please be there.” Thunder claps echo through the halls. Somewhere in a distant room, a door gives out a long, pained creek.

“Gone Home,” an indie adventure game premised entirely on digging through this mansion, searching for answers, begins chillingly.

The game features no external conflict. There are no enemies, no weapons and hardly any puzzles to impede the player’s progress. Instead, it is a game entirely about exploring a house, devoid of people but filled to the brim with evidence about their lives. It is a story-based game in the truest sense.

None of this is to say that this game would be better served as a film or a novel. In fact, the way

“Gone Home” tells its story would be impossible in any other medium.

The narrative is intricately and delicately embedded within the possessions of those who lived there.

From handwritten letters and punk rock mix tapes to a stuffed stegosaurus, everything is immaculately rendered using such high-definition textures that they can be examined within virtual inches of the camera.

This is game in which the player can read, word for word, the ingredients off of a can of ginger ale, if they feel so inclined.

This degree of obsession is not praiseworthy simply for its technical merits, but also for how it allows the game to set scenes and build its characters.

The family’s TV room, for instance, features a solitary pillow fort with a book about communicating with ghosts timidly tucked inside and a grease-stained pizza box sitting not far away. A letter informing Terry Greenbriar, Katie’s father, of crushing news is found discarded below the bar, offering a hint at how he at how he handled the situation.

Many of these moments would not have worked were it not for the game’s spectacular writing, which is surprisingly intelligent and mature.

It isn’t the kind of storytelling that beats the audience over the head with its cleverness, but like everything else in “Gone Home,” the deeper you dig, the more you come to appreciate its full extent.

The game is only about a 3-hour experience, so it’s best to go in as blind as possible; any plot details can damage the experience.

“Gone Home” is just as much about what the player thinks it is as what it really is. As the player discovers more and more things hidden within the house, the game’s tone shifts radically, and these moments are best felt in a raw and instinctual way.

Even the game’s minimalist piano score does little to push you to feel one way or another about what you’re uncovering. Its conclusion is similarly ambiguous: a surprisingly emotional but not-necessarily-happy ending, which forces the player to confront their inability to change an upsetting situation.

“Gone Home” shows that video games are at their best as a storytelling medium when they let their settings do the talking.

And what place has more to say about someone’s dearest loves, their darkest fears and their most intimate secrets than the walls of their home?

It may not be a game for everyone, and it certainly isn’t the game anyone expected of it, but “Gone Home” is a brave experiment that tells a story players won’t soon forget.