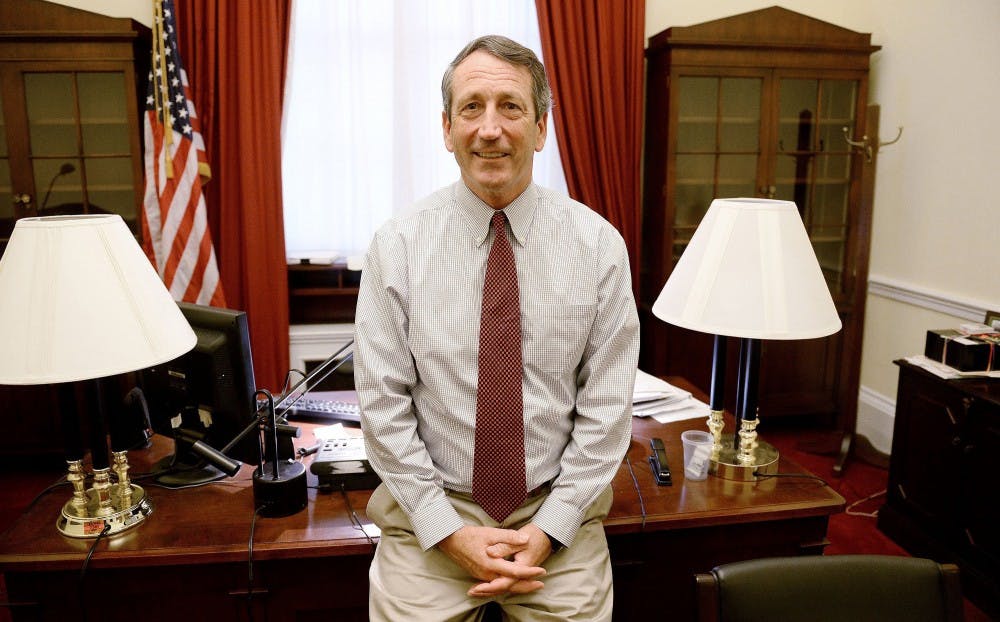

Mark Sanford was no stranger to elections, but, for the first time in his career, he suffered a defeat because of something it once would have been hard to accuse him of — not being conservative enough.

That’s not to say Sanford changed, he’s been pretty consistent in his full-throated support of conservative values, particularly fiscal ones. In fact, Sanford even had the backing of the largest Tea Party organization in the U.S. However, it mattered little in the end. Katie Arrington, with the support of Donald Trump, leveraged Sanford’s public criticism of the president against him, dashing his electoral hopes and, simultaneously, reinforcing the notion that the Republican brand of conservatism has changed irrevocably.

While I have no love for Sanford or his positions, I do think this upset is yet another troubling sign for conservatives in a year full of them. Not Republicans, mind you, but conservatives. Republicans, it seems, have become content with or, at the very least, cowed by Trump and his political brand. Self-proclaimed, capital C conservatives, on the other hand, have faltered and seem almost at a loss of what to do with a party increasingly distancing itself from one of its core tenants.

This shift from a party of conservatives to a party of Trump should worry everyone. If a party, particularly its leader, reacts to internal criticism with purges, the party ends up a mere collection of self-aggrandizing sycophants fighting for scraps of approval.

The best evidence for this is in how Arrington waged her war against Sanford. Instead of playing the all too familiar game of “who’s more conservative,” like with the gubernatorial race this year, she instead focused on what made them different, more specifically, who was more loyal to the president. Say what you will about Sanford, but he, unlike many of his colleagues, laid bare his distaste of the president, even admitting that he was, politically, “a dead man walking” for his open critique.

This insight was not far off the mark, apparently, and Sanford has since called it the primary driver behind his defeat.

What’s important, however, is not how Arrington and Sanford are different but how they are the same. The most important aspect of both, unrepentant conservativism, shone through in both campaigns. So much so that Arrington almost seemed to focus on it more as a simple qualifier of herself than as the flavor of the race. This isn’t particularly surprising, given that Sanford, while outwardly critical of Trump, still voted in favor of bills backed by the president over 70 percent of the time. Even when he voted against bills supported by Trump, they were mainly on the grounds that he simply disagreed, not as some direct, concerted opposition to the president.

Arrington and Sanford, it seems, are both nearly equally as conservative of one another. However, this wasn’t enough for Arrington, who, I suppose, would have been critical of anything but the utmost loyalty to the president. Conservatism didn’t matter, fealty did.

To be clear, I’m not making the case that conservatism in and of itself has changed, but simply that what conservatism means to Republicans has. Republican conservatism, long living under the shadow and moderation of Buckley, strained under the Tea Party and seems to have broken under Trump.

This becomes obvious when you consider that conservatives, in an earlier time, would have balked at paying $21 billion (or, one and a half aircraft carriers) for a wall that won’t even stop the largest form of illegal immigration, visa overstays. Or that conservatives would have turned tail and ran had a Republican president put forward a budget that would add $7 trillion to the national debt in little over a decade. Hell, conservatives would have lost their minds if a Republican president even suggested that we should get closer to Russia despite their continued aggression and support of human rights abusers.

Today, however, that is not the case. Arrington’s endorsement of the entirety of Trump’s agenda clearly wouldn’t be conservative a decade ago, but it is now and that’s a problem.

Despite how sluggish and imperfect our democracy can be, this shift is no fix. Parties standing by their values (or at least policies) serves as a built-in check to the executive by limiting his agenda and preventing flagrant abuses of power. Think of it like parenting. While parents have a lot of control over their kids, kids can and will cause trouble. Now any good parent, when their kid does something wrong, will get the kid to stop and try to put him back on the right track. However, a parent who seeks to be their kid’s friend instead of their parent might just let them continue, no matter how detrimental it is for the kid or the family. A parent who doesn’t take charge may as well not be a parent at all. In the same way, a party whose core value is subservience to the president may as well not be a party but an entourage of bootlickers. Bootlickers, mind you, who will go as far as to defend blatant human rights abuses at the behest of their president.

At the end of the day, this lack of total support for Trump is what killed Sanford. Not his affair, as some will inevitably claim. After all, his district elected him three times despite the specter of the Appalachian Trail hanging over him. No, the shift in the Republican party on the definition of conservative is what did him in.

Unfortunately, he will not be the last old-school conservative to find their once solid base steadily evaporating out from under them. What we’ll be left with then, is yes-men and brown-nosers willing to say whatever it takes to fulfill the will of the president. It’s worth remembering that in politics, the line between brown-noser and Brownshirt is perilously thin.